Lawrence County Archives – Simon Favre

…and their bearing on early slave trade

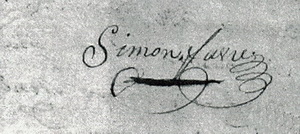

Simon Favre's signature

Simon Favre's signatureAfter several years of arduous research into the history of Hancock County’s most interesting pioneer by my confederate, Dr. Marco Giardino, with only a minimum of assistance by this writer, a bit of luck dropped a cache of papers into my lap. They came from a completely unsuspected county, some distance from Hancock, and even after much study, we cannot be certain why they were housed there. It is evident that they are copies borrowed from New Orleans and Hancock County, sometimes running together even though written years apart.

Dr. Giardino’s article remains a “work in progress,” and when it will be blessed with publisher’s ink, it will be the most authoritative study ever published about Simon Favre, the celebrated interpreter to the Choctaws for the French, British, Spanish and the Americans. Information about early Hancock County history has been hard to come by, primarily because our county seat courthouse burned in 1853.

The new documents constitute a study that stands alone, in great part because it involves information after Favre’s death, and – unlike a scientific study – invites the reader’s speculations.

The repository of the surprise papers is Lawrence County, north by a couple of counties from Hancock. A clue was delivered to me one morning by Jerry Heitzmann, who has been the prime researcher of Favre genealogy to date. It was casual conversation, but he said he had something in his notes which a forgotten informer had told him some years ago. That information said there were papers relating to Simon Favre in Lawrence County.

I planned a trip there, but before going, decided to call to ascertain that there was such a file. A most helpful lady checked and assured me that it was so, and after a little conversation, she generously offered to mail me copies.

They are welcome additions to the total picture of Simon Favre, adding much to what we previously knew but concurrently introducing questions with no evident answers

Enter the Louisiana Slave Database

About the same time, we were fortunate to become aware of The Louisiana Slave Database, 1719-1820, by Dr. Gwendolyn Midlo Hall. Her in-depth study makes it possible to explain and understand some of the revelations of the Lawrence County papers. The Louisiana records of sales of slaves by Simon Favre during later life and of those sold by his estate, apparently in slave auctions, prove invaluable to the study of a Mississippi plantation and its subsequent inclusion in an estate administration. Appropriate mention of these facts will be included in the analysis that follows.

The major addition to knowledge of Simon Favre comes in the inclusion of an unknown plantation, the name of which is illegible but appears to be “Storepem,” and a list of 57 slaves not mentioned in his will. It may be that he had just bought the plantation and slaves shortly before he died, as it is not likely that he would have ignored values like these in making his will.

Related Documents

The more important Lawrence County documents include the following:

- English translations of will, will dated 5-18-12

- Second translation of will, with cover memo by James Pitot, judge, dated at New Orleans 7-20-1813

- French will

- Marriage certificate, signed by Fra Antonio Sedella in New Orleans

- Copy of records from Hancock County, certified by Roderick Seal 12-30-44, including inventory of personal property

- Appraisers’ report dated 6-15-14, referred to as “Second Inventory,” which includes lands

Index of dates

An index of dates may be of service to a reader. The ones of most significance are:

Feb. 5, 1800 – Simon Favre’s son by Rebecca Austin born

Mar. 24, 1801 – Slave exchange between Simon and Rebecca

Mar. 25, 1801 – Marriage of Simon and Celeste Rochon

Aug. 2, 1802 – first child born to Simon and Celeste

May 18, 1812 – Simon’s will

April 1812 – likely purchase of plantation

June 3, 1813 – death of Simon Favre

June 15, 1814 – inventory of personal property

Oct. 5, 1814 – second inventory

1820 (approx.) – marriage of the widow Favre to Isaac Granves

Nov. 1827 – final decree of estate

The Will

Certainly among the most important documents in the Lawrence County collection is the will of Simon Favre, in the form of copies of the original French and two English translations. While a copy of the will was known before, these documents appear in some ways to be more precise.

Favre wrote his will on May 18, 1812, scarcely a year before his death. He listed his wife Celeste and his children, and included a special provision for his son Simon Austin by a previous relationship. He also carefully documented his land holdings, and mentioned his debts in such a way as to consider them insignificant.

Lands listed are as follows (notes in parentheses are editor’s explanations):

- English grant – 1200 arpents on Small Pearl River – from father (This parcel has to be what is shown in American State Papers A-No.2, original claimant J.C. Favre, a British patent dated 10 April 1771, in St. Tammany Parish, LA. It was surveyed in 1775 by E. Dernford, later signed by Pintado.) 1

- 800 arpents on large Pearl – from father

- 1200 arpents on large Pearl – from English government

- 800 arpents from Spanish government, “and likewise that I cultivate on the Island” (2nd copy of will says “also one” instead of “likewise.” It seems this is the only one identified as being from Spanish, and is probably the parcel described in AMP Report No. 4 as 1200 acres east of Pearl River, claimed on March 5, 1804.

- 800 arpents at the place called Oncaya (2nd Inventory identifies this as “the Island between the two Pearl Rivers.)

- one likewise at Mobile of 400 arpents that I purchased from Simon Endy

- 400 arpents on the upper part of the river at la Boutille (spelled Bouticelle in 2nd will, and Boutille in French will) from my father, English grant (I have checked to see if there is such a French word, but found none)

- Also the lands given to me by the Indians on river Tombechbe

Noteworthy about the will is the absence of a list and valuation of the decedent’s slaves. Inclusion is customary for wills of the period for reasons that their value normally exceeds other assets. For this reason, they often are listed first, before cattle, land, and other values.

After his death, an appraisal for his estate listed 57 slaves valued at $14,695, a very substantial asset not to have been mentioned in the will.

Inventory and Appraisement of Assets

It seems clear that Favre died in Hancock County, but documents essential to the distribution of his estate had been filed in New Orleans, as well as in his home state, probably with his attorney, Rutilius Pray of Pearlington, MS.

New information revealed in the Lawrence County papers is to be found primarily in the documents dated June 15 and October 5, 1814. The first is the summary of the appraisement of the inventory, and for the first time, there is an inclusion of slaves as having been owned by Simon Favre. It is signed by Joseph Chalon, Mathurin Babin, John Williams, and Noel Jourdan, all important figures in Hancock County.

Called the “Inventory of Personal Property,” it begins with a list by name and age of the 57 slaves. The first is an 80-year old, valued at only $5.00. The most valuable is Isidor, age 30 and a “cow hunter” at $900. Rosette was a “negroe Wench house servant 25 years of age.” Total value of slaves was $14,695. (Subsequent appraisal in the estate was for only 56 slaves, for the identical value; it apparently left out the 80-year old.)

Next came the cattle, and then the horses, saddles, 30-ton schooner, etc. for a grand total of personal estate of $20,326.

Mention is made that the real estate had been eliminated from the appraisal “because the greater part of it…is at a great distance from this place” and that the appraisers have no knowledge of the worth of the parcels, “and further that the sale of the real estate cannot be made not till an order by giving [sic] by the legislature….” This statement may have referred to the three pieces in and near Mobile.

The 9th Parcel – a Plantation New to the Estate

The next document of importance is the “Second Inventory,” dated October 5, 1814. It was completed at the Pearlington plantation of Celeste Rochon, widow of Simon Favre, and appointed the same appraisers as above, adding one, Louis Geuses [Gause?]. Various assets were listed, beginning with “2 pair of Broken Oxen” at $60, and continuing through pots and kitchen furniture at $10. Following such was then listed lands, to which a 9th parcel was added to the previously known pieces. Values of the lands, ranging from 800 to 1200 arpents, were from $200 to $300, with the exception of the last, the 9th, measuring 800 arpents, with improvements, and valued at $500. As stated above, the name of the latter is illegible, but appears to be “Storepem.”

Total of arpents was 6,200. Total value was listed at $2,410. Signatures were those of Babin, Jourdan, and J. Baptiste Daube.

Jourdan acknowledged a mistake in the first appraisement in that it included 450 head of cattle, whereas it should have been 225, as the other 225 belonged to the children.

The location of the plantation referred to in the estate inventory as the 9th parcel has not been established with certainty, but it might also have been known as Hickory Camp Creek, just down river from Napoleon. Whatever its name, it could be that it was purchased just before Favre wrote his will (May 18, 1812), and conceivably transfer had not been finalized. When he died there may still have been no completed deed.

Following a signature of Noel Jourdan on a document dated July 5, 1814, there is another document with an uncertain date. Mentioning only “the 5th of the present month,” it is a petition by the much honored Rutilius Pray, attorney the widow Favre, asking the court of Hancock County to allow sale of some of assets, stating that widow Favre “would desire to avoid the law suits and costs if possible as they always put a family in distress…to satisfy divers creditors that might present themselves against her….” Widow Favre declared that she had “a perfect knowledge” of notes and accounts amounting to $8,765, and proposed to be allowed to sell “a schooner with the negroes Ben and Michael Challenelle’s family of seven head honore family of nine head Louis Quintin, Osman, Pierre Congo, also one hundred and sixty cows and thirty mares and young horses.” [sic]

[NB: Some of the names in the foregoing will be seen later in the study of the sales of slaves by Favre and his estate. From those records, Celeste did not sell all that she asked to sell. In point of fact, Ben, age 50, was sold for $405, separately from his family.]

The petition continued, suggesting that the judge “will please to order the advertisement of the above mentioned articles….”

Order to Pay Legacy – 1824

From this point, the documents skip from 1814 to ten years later. Following the October 1814 document, papers are run together continuously as though part of one document. The next is an “Order to pay legacy,” dated August 14, 1824. It is at this point that it becomes apparent that the above actions were being reviewed for a civil action with copied documents involving Simon Favre, Jr., son of Rebecca Austin, with whom Favre had a relationship before his marriage to Celeste Rochon.

The later document is a restatement of that part of Favre’s will which left to his son $1500 “to be paid out of the proceeds of the estate…at such time as he shall arrive at the age of majority” and that “he has arrived at the age aforementioned.”

On the date above, Simon Jr. had come of age and swore that he has not received any part of the amount promised.

Subsequently, at the February 1825 session of the court, on motion by Rutilius Pray for Isaac Graves and his wife Celeste (now married), the above decree was set aside. The reason, in part, was that the estate’s costs have not been settled, according to Isacc and Celeste Graves. In addition, there was a complication introduced in that young Simon had assigned his benefits to one Jesse Depew, which fact had not been disclosed to Celeste. She and Graves therefore filed suit against Depew. At this point, they also filed for a partition of real estate consisting of a parcel at the lower end of Pearlington, measuring 40 by 40 arpents, “agreeable to a plan made by Elihiu Carver.” This, together with the next petition, may have been a maneuver to separate out lands that might have been attached by Simon Austin or his assigns.

On July 12, 1826, Graves made a “petition for dower.” This was a request that the “tract of land at Pearlington” be considered separate from the lands belonging to the other heirs. On May 2, 1826, Isaac and Celeste signed a statement reading, “The accounts of the testamentary executors of Simon Favre will be reported to the next term of the County and Probate Court of the County of Hancock.”

Credits and Debits – 1826

It was then that a final statement of the executors of the estate of Simon Favre was presented by Rutilius Pray. Submitted to the court for its October 1826 term, it was headed “Exposition” and divided into parts A, B, and C.

Part A was a valuation of what was perceived to be the worth or assets including slaves, cattle, horses, a schooner and lands, the latter being only $1,800.

Pray’s detailed accounting showed “appraisements” to include the following:

56 slaves – $14,695

225 head cattle 1550

50 head of horse 1025

Schooner 1505

Lands 1800

Total: 20,575

Next came what appears to have been July 25, 1814 “sales” of some of the same items, but also an October 24 sale for $1,000 of “Plantation Storepem.” [Editor’s note: the name is still uncertain.] If in fact there had been a sale of the plantation, there is nothing to indicate who the buyer was.

The total sales including cattle, horses, slaves and the plantation was in the amount $26,956, the largest being that of slaves, amounting to $21,870.

Part B of the Exposition lists substantial debts. This also is at variance with the will, which appears to treat debts lightly, referring to them simply as, “I have some debts which I enjoin my testamentary Executor to pay….”

In contrast, the Exposition is more explicit, listing nine for a total of $32,885.99¼. The largest was $15,932, perhaps still owing for slaves.

One item that stands out in the above figures is that the Mississippi estimate, made by landed neighbors and ranking officials, was far lower than the actual sale value. This is even more remarkable when considering that the estimate was for 56 slaves, whereas the sale was far fewer. As is well known, plantation owners up and down the Mississippi River were crying for more slaves. It is evident that the market in New Orleans was stronger than that of Hancock County, and that an auction commanded higher prices than individual sales. The executors were wise to bring to market called in New Orleans what the widow Favre called “articles.”

Part C again recites the receipts from sales, adding $1,500 for 400 arpents in Mobile and lesser amounts for two small sites, and then claims disbursements of the $32,885.99 ¼.

Estate Solvent

On balance, the estate appears to have been solvent. The total amount of the debt is shown to have been disbursed in an 1826 filing with the court. This is still confusing, because the Exposition does not show receipts and pay-out in balance. The court stated that the commissioners had accounted for land totaling 2,840 acres and considered that this was to be available for payment of shortfall. In fact, Pray seems to have made a formal petition to that effect.

Pray charged fee of 8% on inventory, equal to $1,646, inventory being equal to appraisement of 20,575.

Final Decree – 1827

In the November term of 1827, another decree was made. In stating “the prayer of the petitioner is granted,” it also recited “Sale has been made of all the remaining lands belonging to the said estate.” An accounting shows that four parcels were sold, as follows:

- Tract of 600 arpents on West Pearl in Louisiana (buyer Benjamin Singlelary for $600)

- Tract of 640 acres on East bank of Pearl at place called the waist house

- Tract of 958 acres on East Pearl, called Favre’s Old Place

- Tract of 640 acres on Pearl River at Walkaya Bluff

Numbers 2, 3, and 4 bought by Isaac Graves for total of $1,740. Noel Jourdan was acting auctioneer.

Included was a sworn statement of Calvin Merrill dated October 14, 1824, to effect that the Graves had sold several tracts of land belonging to the estate, one being in Mobile and two others on Pearl River. Merrill was judge of probate in Hancock County. He was “duly sworn on the holy evangelist.”

More about “the 9th Parcel”

The location of the plantation referred to in the estate inventory as the 9th parcel has not been established with certainty, but it might have been at Hickory Camp Creek, just down river from Napoleon. It must have been purchased just before the date of Favre’s will (May 18, 1812), and conceivably transfer had not been finalized. United States Public Land No. 322 shows “Hickory Camp Creek” as having been originally settled in April 1812 with the original and present claimant (as of November 1819) said to be John Bte. Favre. The date of settlement – April 1812 – was within one month of Favre’s writing of his will. His oldest son, named Jean Baptiste, would have only been age ten at the time, and so it may have been Simon’s bother, Batiste Favre, who took possession, perhaps as a family representative. It is possible that this in someway ties in with the October 24 sale, above.

Later, in the 1829 Tax Rolls of Hancock County, Jean Baptiste Favre is still carried as owner, referring to a parcel of 640 acres as “Hickory Camp.” This is possibly the 640 acre tract shown in later maps as being owned by “representatives” of Simon Favre. It is located just south (down river) from Napoleon.

Slave Sales Prior to Favre’s Death

Besides the list of estate sales of Favre’s slaves, Dr. Hall’s research also makes possible the finding of a number of sales and purchases during Favre’s lifetime. These cover a period between 1801 and 1811, and once more there is a question of why the purchases were not in the will. It is, of course, possible that he had sold them and/or some had died.

Among the interesting transactions of the earlier period are those involving Rebecca Austin, sometimes thought to have been Favre’s black wife.

If the sales involving Rebecca as owner do not reflect her as being a free black, it would be usual to assume that she must have been white. After all, other owners are shown to be free blacks. At least in one document, the one she signed with Simon regarding the several slave transfers, she signed legibly, indicating she may have been literate. Moreover, in an estate sale of one of those below, she obviously was deceased and represented by a testamentary executor.

Summary of slave transactions between Favre and Rebecca:

Doc. 53: Favre sold to Rebecca Henriqueta, F32, Betty, 6, and infant F,

Value: $1,000, on 2-20-01

Doc. 95: Favre sold Constanza, F20 and Ortanza, F 10,

Value: zero, on 3-24-01

Latter is said by Dr. Hall to be an exchange of those in Doc. 53 for those Rebecca’s slaves in Doc. 95. This is confusing to me as Rebecca wound up as owner of all five. It causes one to wonder whether Favre bought from Horton (mentioned in Hall account) and immediately gave to Rebecca. (In these papers the name Rosalia Harton is mentioned as owner. While this is confusing, it may be a misinterpretation of the last name for Ortin or Austin, as Rebecca has been know to go by the first name Rosalia; cf baptism of her son.)

These exchanges are curious. They occurred just about a year after Rebecca’s son Simon, Jr. was born (February15, 1800) and about the time of the marriage of Favre to Celeste Rochon. To be specific, the sale was one day Favre and Celeste were married in the Cathedral at New Orleans.

It would seem that Simon had to make a choice and therefore parted company with Rebecca. Perhaps the slaves were a peace offering, or on the other hand, he was seeing that she would have help in raising his son.

The later sales during Favre’s lifetime, in 1811, as well as some by the estate in 1814, confuse the above. (It is observed that Spanish forms of names are used in the early sales, while French names appear in the estate sale.) Slaves who had been transferred to Rebecca Austin appear in these transactions:

Hortense, (Ortanza) was sold back to Favre by Blanche. (1811)

Constance (Constanza) and Louis (Luis) were sold by estate to St. Amant. (1814)

Betty, age 18, was sold to Duplantier along with Charles, age 12, possibly the unknown infant (girl?). (1814)

Honorato (Honore) was sold to Poeyfarre. (1814)

The question arises, how could these slaves have belonged to Rebecca and end up in Favre estate? One answer is that Rebecca had died, and Simon bought Hortence and her two children, Regis, 5, and Louise, 1, from her testamentary executor, Jean Joseph Blanche. Date of sale was March 16, 1811. (Efforts to find her date of death have been without success.)

Lifetime Sales by Document number

10 – Dique (cooper) male, Favre/Idalgo

53 – Henriqueta, Betty, (unnamed), Favre/Ousten (3 females)

95 – Constanza, Ortanza, f,f, Favre/Ousten

61 – Chalineta , f, Favre/Broutin

697 – Adelayda, Teodulo, m,f, Favre/Broutin

1802

280 – Telemaco, m, Favre/Mothere

299 – Luis, m, Favre/Mazenge

346 – Honorato, m, Favre/Fortin

573 – Pedro, m, Favre/Broutin

1808

103 – Marie, f, Favre/Neda

1811

54 – Hortence, Regis, Louise, f,m,f, Favre/Blanche

Slave sales by the Estate

Dr. Hall’s list of sales for 1814 produces only $15,685 for 35 slaves. We have no record of sales for rest of slaves. What seems to be missing is the sale of slaves other than the 35 for which we have Dr. Hall’s record. A guess might involve Isaac Graves. He had no slaves in 1820 census, but 41 in 1830 and 1840

1814 Sales by Estate – by document number

330 – Evariste,

332 – Benn

331 – Marie, Charles, Isabelle, Rose

335 – Julie, #9, Henry

337 – Rosalie

339 – Julie, Charlotte

340 – Paul

344 – Quinto

348 – Honore

350 – Constance, Desiree, Thedore, Regis, Louise

350 – Regis

352 – Osmano

354 – Rosette, Henry, Charles, Betty, Charles

361 – Helene, #9

362 – Congo Pierre.

362 – Henriette, Suzanne, Renette, Arsene, Francois

A Concluding Observation: Favre and New Orleans

In the listing of new documents at the beginning of this article, there is mention of a memo written by James Pitot, judge in New Orleans. It is treated here separately from other information because, unlike factual data, it invites some speculation. In particular, it suggests Favre’s relationship to New Orleans may have more than as a resident of a neighboring state.

It precedes an English translation of Favre’s will, and reads partially: “…personally appeared before me, James Pitot, Judge of the Court of Probates, in and for the Parish of New Orleans, Pierre Caraby and Don Martin Pellerin, both residents of the Parish of New Orleans, who being sworn agreeable to law declare and say that a packet folded up as a letter, sealed with three red wafers, which I presented to them and bearing the following subscription: ‘I declare that this packet containing my testament and last will that I deposit in the hands of [illegible] Narcise Broutin, my friend, recommending to him to render it public as soon as decease takes place. New Orleans, May 18, 1812. Simon Favre’”

There is no doubt that Favre was a resident of Mississippi for many years, spending a career as a translator to the Choctaws, and that he made his home in Hancock County probably at least from the time of his marriage to Celeste. However, so much of his life and so many of his important events having been tied to New Orleans, one must wonder whether he wanted to be considered a New Orleans resident.

In addition to the above, several other items are worth consideration:

…..His illegitimate son, Simon Jr., said to have been born of Rosalia Ostein on February 5, 1800, was baptized in New Orleans at the Cathedral on February 18, 1800. While Fra Sedella listed her as native of Mobile, he wrote that Favre was “a native of this city.”

….His marriage took place in the Cathedral of New Orleans and was officiated by Antonio Sedella, the beloved rector better known to his followers as Pere Antoine. In that document, dated March 25, 1801, he was said to be a resident of Mobile.

….He named Fergus and Armand Duplantier, two prominent Louisianans, in his will, as curator for his children and as executor of the estate. (Later, Celeste and Isaac Graves were successful in having Fergus and apparently Armand removed from any official capacity because they were residents of Louisiana and therefore said to be unable to serve in Mississippi.)

….He dealt in the New Orleans slave market, including sales to the notary, Narcisse Broutin, his “friend,” to whom the above described packet was entrusted.

….His obituary was published by a New Orleans French/English newspaper on July 20, 1813, shortly after his death of July 3, although it listed Mobile under “notes.”

While it must be considered that Hancock County was not as much a center for business and legal activity as New Orleans, there may have been other reasons for Favre’s preferences, such as the politics of the time. If nothing more, Favre’s associations with the prominent officials and property owners of Louisiana point to his status as someone accepted as a person of high rank.

Question: Is there more on Simon Austin?

The Lawrence County documents end with the last mentioned, i.e. the decree of 1827. Unfortunately, there is nothing more to tell what happened to the claim of Simon Austin or of his assigns. Perhaps they are housed in another file, in which case a new challenge awaits someone. Other, seemingly unrelated papers in this file date as late as 1847, possibly indicating that there had not been any closure with regard to Simon Farve’s wishes for his son as stated in his will.

Other Notes of Interest

Many important people of the time signed various papers: Chalon, Mathurin Babin, Noel Jourdan, Isaac Graves, John B. Toulme, Pray, Edwin Russ, Ripley, A.B. Roman. Also found is name of Judge Pitot, first mayor of incorporated New Orleans.

Certificate of marriage was witnessed by Antonio Sedella, who was the beloved priest of the St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans, known affectionately in history as Pere Antoine.

Suits involving the estate

Sales of 1814 were not without complications. Below are some of the suits that resulted:

Docket 752, 1st Judicial District Ct. of Orleans – Widow F. and Jos. Chalon, listed as “both of Mobile,” testamentary executors Vs. Neda Sifroy Dolive 6-6-1815

Suit for $408 for prom note dating from 9-1-14

Judgment For Plaintiff with int @5%

Answer by Defendant: they were both debtors and creditors, and were owed more than debt.

Docket 835, same ct as above – filed 31 July 1815 – petition of Jos. Chalon and Widow Favre, both of Mobile, execs. of Simon F. : a certain Auguste Peytavin of state of LA was indebted by promissory note for $340. from Sept. 24, 1814. Note signed by Peytavin but endorsed by L.M. Reynaud. [Exposition shows date of slave sale July 25, 1814.]

Answer by Peytavin: The consideration for which he gave note has failed, for this, that this def. purchased a Negro at the public sale of slaves belonging to the est. of F. and that the Negro is subject to disability, viz., running away, for which defendant has brought against Plaintiff [illegible] action before this court.

P.L. Monet for Defendant

Sept. 5, 1815 – Peytavin ordered to appear in court July 31, 1815.

About Slavery in Louisiana

Slave importation into Louisiana was supposed to have been made illegal under the terms of the Purchase. For this reason, I have been reading about the effect of Jefferson’s limiting of slavery in the Purchase, and the conclusion is that Congress had made enough accommodations that it had no effect. Roger Kennedy in Common-Place, says Jefferson had given his OK to language prepared by Pickering that “would have prohibited slavery in all territories between the Appalachians and the Mississippi except Kentucky. It failed by one vote.” That vote was Monroe’s. It was he who “presided over the final negotiations for the Purchase, in which was inserted the fatal language assuring, in the interpretation of the Jeffersonian Congress, the rights to hold and to import slaves into the vast dominion included in the Louisiana Purchase.”

rbg

1 Confirmed by list of claims west of Pearl River, A-No. 2. Cf Marco’s attachment, email of 7/20/09.