This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

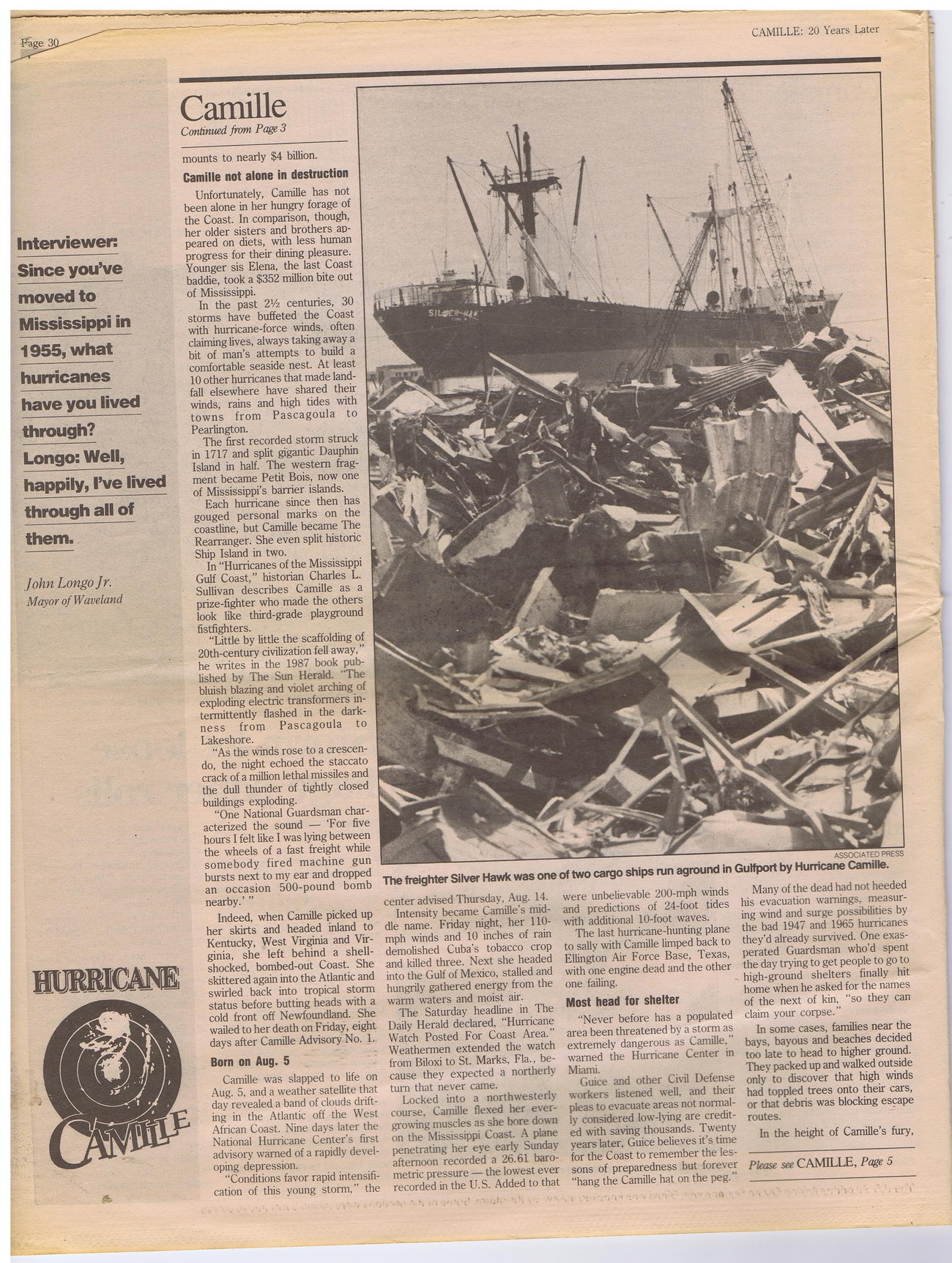

Page 31 CAMILLE: 20 Years Later Interviewer: Since you’ve moved to Mississippi in 1955, what hurricanes have you lived through? Longo: Well, happily, I’ve lived through all of them. John Longo Jr. Mayor of Waveland ASSOCIATED PRESS The freighter Silver Hawk was one of two cargo ships run aground in Gulfport by Hurricane Camille. Camille Continued from Page 3 mounts to nearly $4 billion. Camille not alone in destruction Unfortunately, Camille has not been alone in her hungry forage of the Coast. In comparison, though, her older sisters and brothers appeared on diets, with less human progress for their dining pleasure. Younger sis Elena, the last Coast baddie, took a $352 million bite out of Mississippi. In the past 2xh centuries, 30 storms have buffeted the Coast with hurricane-force winds, often claiming lives, always taking away a bit of man’s attempts to build a comfortable seaside nest. At least 10 other hurricanes that made landfall elsewhere have shared their winds, rains and high tides with towns from Pascagoula to Pearlington. The first recorded storm struck in 1717 and split gigantic Dauphin Island in half. The western fragment became Petit Bois, now one of Mississippi’s barrier islands. Each hurricane since then has gouged personal marks on the coastline, but Camille became The Rearranger. She even split historic Ship Island in two. In “Hurricanes of the Mississippi Gulf Coast,” historian Charles L. Sullivan describes Camille as a prize-fighter who made the others look like third-grade playground fistfighters. “Little by little the scaffolding of 20th-century civilization fell away,” he writes in the 1987 book published by The Sun Herald. “The bluish blazing and violet arching of exploding electric transformers intermittently flashed in the darkness from Pascagoula to Lakeshore. “As the winds rose to a crescendo, the night echoed the staccato crack of a million lethal missiles and the dull thunder of tightly closed buildings exploding. “One National Guardsman characterized the sound — ‘For five hours I felt like I was lying between the wheels of a fast freight while somebody fired machine gun bursts next to my ear and dropped an occasion 500-pound bomb nearby.’ ” Indeed, when Camille picked up her skirts and headed inland to Kentucky, West Virginia and Virginia, she left behind a shellshocked, bombed-out Coast. She skittered again into the Atlantic and swirled back into tropical storm status before butting heads with a cold front off Newfoundland. She wailed to her death on Friday, eight days after Camille Advisory No. 1. Born on Aug. 5 Camille was slapped to life on Aug. 5, and a weather satellite that day revealed a band of clouds drifting in the Atlantic off the West African Coast. Nine days later the National Hurricane Center’s first advisory warned of a rapidly developing depression. “Conditions favor rapid intensification of this young storm,” the center advised Thursday, Aug. 14. Intensity became Carnille’s middle name. Friday night, her 110-mph winds and 10 inches of rain demolished Cuba's tobacco crop and killed three. Next she headed into the Gulf of Mexico, stalled and hungrily gathered energy from the warm waters and moist air. The Saturday headline in The Daily Herald declared, “Hurricane Watch Posted For Coast Area.” Weathermen extended the watch from Biloxi to St. Marks, Fla., because they expected a northerly turn that never came. Locked into a northwesterly course, Camille flexed her evergrowing muscles as she bore down on the Mississippi Coast. A plane penetrating her eye early Sunday afternoon recorded a 26.61 barometric pressure — the lowest ever recorded in the U.S. Added to that were unbelievable 200-mph winds and predictions of 24-foot tides with additional 10-foot waves. The last hurricane-hunting plane to sally with Camille limped back to Ellington Air Force Base, Texas, with one engine dead and the other one failing. Most head for shelter “Never before has a populated area been threatened by a storm as extremely dangerous as Camille," warned the Hurricane Center in Miami. Guice and other Civil Defense workers listened well, and their pleas to evacuate areas not normally considered low-lying are credited with saving thousands. Twenty years later, Guice believes it’s time for the Coast to remember the lessons of preparedness but forever “hang the Camille hat on the peg. ’’ Many of the dead had not heeded his evacuation warnings, measuring wind and surge possibilities by the bad 1947 and 1965 hurricanes they’d already survived. One exasperated Guardsman who’d spent the day trying to get people to go to high-ground shelters finally hit home when he asked for the names of the next of kin, “so they can claim your corpse.” In some cases, families near the bays, bayous and beaches decided too late to head to higher ground. They packed up and walked outside only to discover that high winds had toppled trees onto their cars, or that debris was blocking escape routes. In the height of Camille’s fury, Please see CAMILLE, Page 5

Hurricane Camille Camille-20-Years-Later (04)