This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

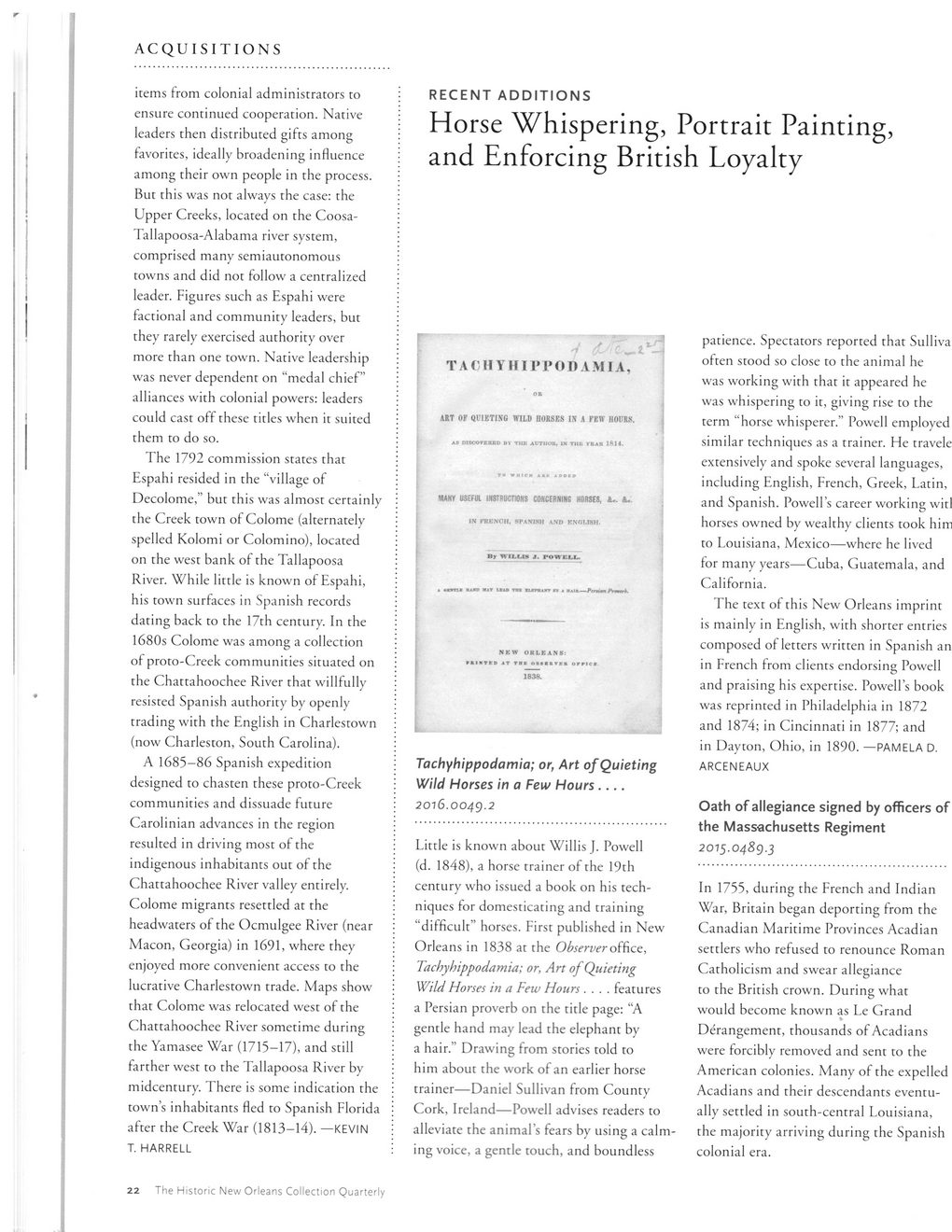

ACQUISITIONS RECENT ADDITIONS Horse Whispering, Portrait Painting, and Enforcing British Loyalty items from colonial administrators to ensure continued cooperation. Native leaders then distributed gifts among favorites, ideally broadening influence among their own people in the process. But this was not always the case: the Upper Creeks, located on the Coosa-Tallapoosa-Alabama river system, comprised many semiautonomous towns and did not follow a centralized leader. Figures such as Espahi were factional and community leaders, but they rarely exercised authority over more than one town. Native leadership was never dependent on “medal chief” alliances with colonial powers: leaders could cast off these titles when it suited them to do so. The 1792 commission states that Espahi resided in the “village of Decolome,” but this was almost certainly the Creek town of Colome (alternately spelled Kolomi or Colomino), located on the west bank of the Tallapoosa River. While little is known of Espahi, his town surfaces in Spanish records dating back to the 17th century. In the 1680s Colome was among a collection of proto-Creek communities situated on the Chattahoochee River that willfully resisted Spanish authority by openly trading with the English in Charlestown (now Charleston, South Carolina). A 1685-86 Spanish expedition designed to chasten these proto-Creek communities and dissuade future Carolinian advances in the region resulted in driving most of the indigenous inhabitants out of the Chattahoochee River valley entirely. Colome migrants resettled at the headwaters of the Ocmulgee River (near Macon, Georgia) in 1691, where they enjoyed more convenient access to the lucrative Charlestown trade. Maps show that Colome was relocated west of the Chattahoochee River sometime during the Yamasee War (1715-17), and still farther west to the Tallapoosa River by midcentury. There is some indication the town’s inhabitants fled to Spanish Florida after the Creek War (1813-14). —KEVIN T. HARRELL T A CII Y II11*1*0 D AM I A, OK ART OF QUIETING WILD HORSES IK A PEW HOURS. MANY USEFUL INSTRUCTIONS COMCEfiMNfi HORSES, JU. IN KBKNCH. SPANISH AND KNfll.ISH. Hr WILUN J. POWELL. < «mi BAMS MAT UA» TOT lUMDfT ST * ■<■ Prmtrk. NKW ORLEANS: 1836. Tachyhippodamia; or, Art of Quieting Wild Horses in a Few Hours.... 2016.0049.2 Little is known about Willis J. Powell (d. 1848), a horse trainer of the 19th century who issued a book on his techniques for domesticating and training “difficult” horses. First published in New Orleans in 1838 at the Observer office, Tachyhippodamia; or, Art of Quieting Wild Horses in a Few Hours .... features a Persian proverb on the title page: “A gentle hand may lead the elephant by a hair.” Drawing from stories told to him about the work of an earlier horse trainer—Daniel Sullivan from County Cork, Ireland—Powell advises readers to alleviate the animal’s fears by using a calming voice, a gentle touch, and boundless patience. Spectators reported that Sulliva often stood so close to the animal he was working with that it appeared he was whispering to it, giving rise to the term “horse whisperer.” Powell employed similar techniques as a trainer. He travele extensively and spoke several languages, including English, French, Greek, Latin, and Spanish. Powell’s career working witl horses owned by wealthy clients took him to Louisiana, Mexico—where he lived for many years—Cuba, Guatemala, and California. The text of this New Orleans imprint is mainly in English, with shorter entries composed of letters written in Spanish an in French from clients endorsing Powell and praising his expertise. Powell’s book was reprinted in Philadelphia in 1872 and 1874; in Cincinnati in 1877; and in Dayton, Ohio, in 1890. —PAMELA D. ARCENEAUX Oath of allegiance signed by officers of the Massachusetts Regiment 2075.0489.3 In 1755, during the French and Indian War, Britain began deporting from the Canadian Maritime Provinces Acadian settlers who refused to renounce Roman Catholicism and swear allegiance to the British crown. During what would become known as Le Grand Derangement, thousands of Acadians were forcibly removed and sent to the American colonies. Many of the expelled Acadians and their descendants eventually settled in south-central Louisiana, the majority arriving during the Spanish colonial era. 22 The Historic New Orleans Collection Quarterly

New Orleans Quarterly 2016 Summer (019)