This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

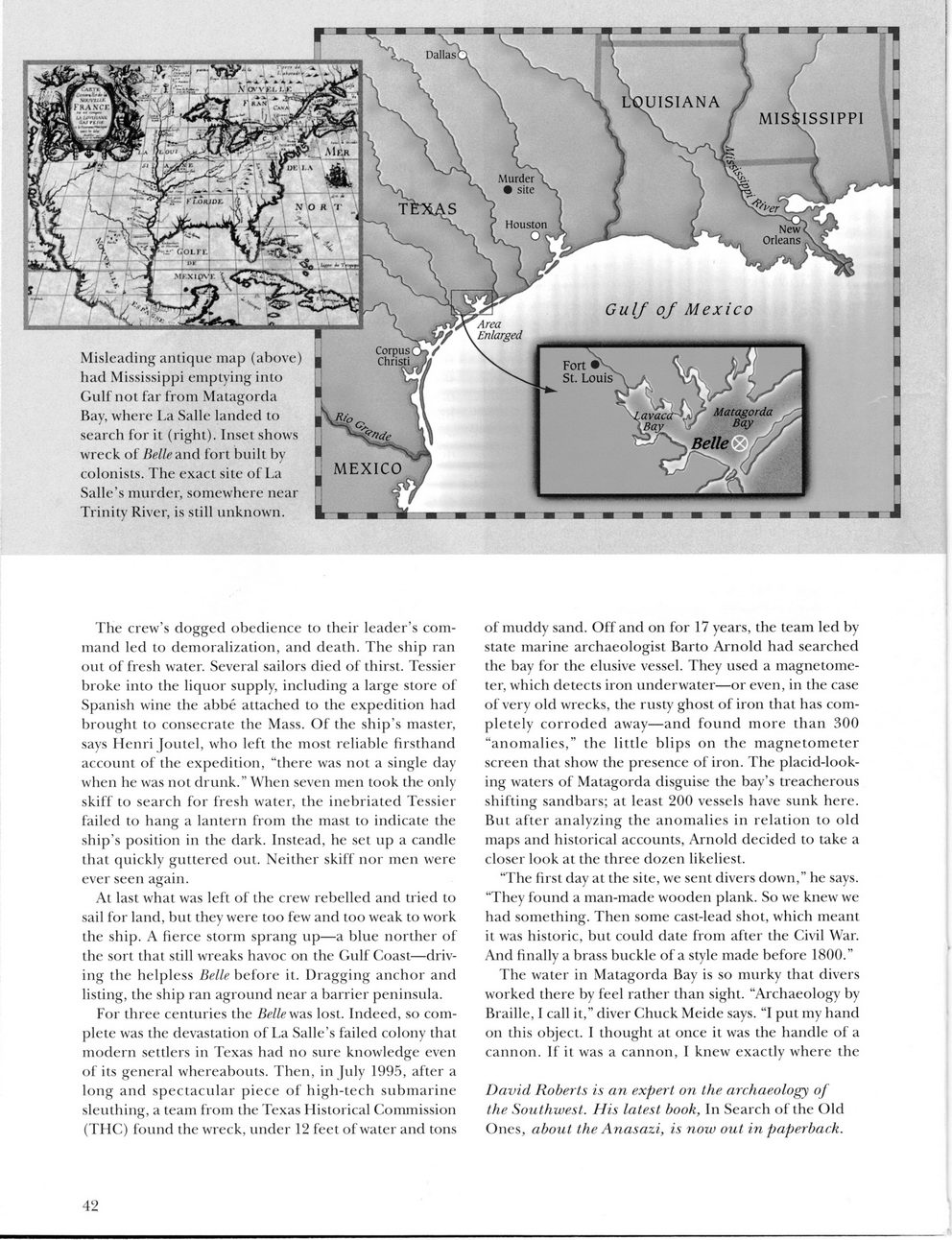

Misleading antique map (above) had Mississippi emptying into Gulf not far from Matagorda Bay, where La Salle landed to search for it (right). Inset shows wreck of Belle and fort built by colonists. The exact site of La Salle?s murder, somewhere near Trinity River, is still unknown. The crew?s dogged obedience to their leader?s command led to demoralization, and death. The ship ran out of fresh water. Several sailors died of thirst. Tessier broke into the liquor supply, including a large store of Spanish wine the abbe attached to the expedition had brought to consecrate the Mass. Of the ship?s master, says Henri Joutel, who left the most reliable firsthand account of the expedition, ?there was not a single day when he was not drunk.? When seven men took the only skiff to search for fresh water, the inebriated Tessier failed to hang a lantern from the mast to indicate the ship?s position in the dark. Instead, he set up a candle that quickly guttered out. Neither skiff nor men were ever seen again. At last what was left of the crew rebelled and tried to sail for land, but they were too few and too weak to work the ship. A fierce storm sprang up?a blue norther of the sort that still wreaks havoc on the Gulf Coast?driving the helpless Belle before it. Dragging anchor and listing, the ship ran aground near a barrier peninsula. For three centuries the Belle was lost. Indeed, so complete was the devastation of La Salle?s failed colony that modern settlers in Texas had no sure knowledge even of its general whereabouts. Then, in July 1995, after a long and spectacular piece of high-tech submarine sleuthing, a team from the Texas Historical Commission (THC) found the wreck, under 12 feet of water and tons of muddy sand. Off and on for 17 years, the team led by state marine archaeologist Barto Arnold had searched the bay for the elusive vessel. They used a magnetometer, which detects iron underwater?or even, in the case of very old wrecks, the rusty ghost of iron that has completely corroded away?and found more than 300 ?anomalies,? the little blips on the magnetometer screen that show the presence of iron. The placid-look-ing waters of Matagorda disguise the bay?s treacherous shifting sandbars; at least 200 vessels have sunk here. But after analyzing the anomalies in relation to old maps and historical accounts, Arnold decided to take a closer look at the three dozen likeliest. ?The first day at the site, we sent divers down,? he says. ?They found a man-made wooden plank. So we knew we had something. Then some cast-lead shot, which meant it was historic, but could date from after the Civil War. And finally a brass buckle of a style made before 1800.? The water in Matagorda Bay is so murky that divers worked there by feel rather than sight. ?Archaeology by Braille, I call it,? diver Chuck Meide says. ?I put my hand on this object. I thought at once it was the handle of a cannon. If it was a cannon, I knew exactly where the David Roberts is an expert on the archaeology of the Southwest. His latest book, In Search of the Old Ones, about the Anasazi, is now out in paperback. 42

LaSalle 003