This text was obtained via automated optical character recognition.

It has not been edited and may therefore contain several errors.

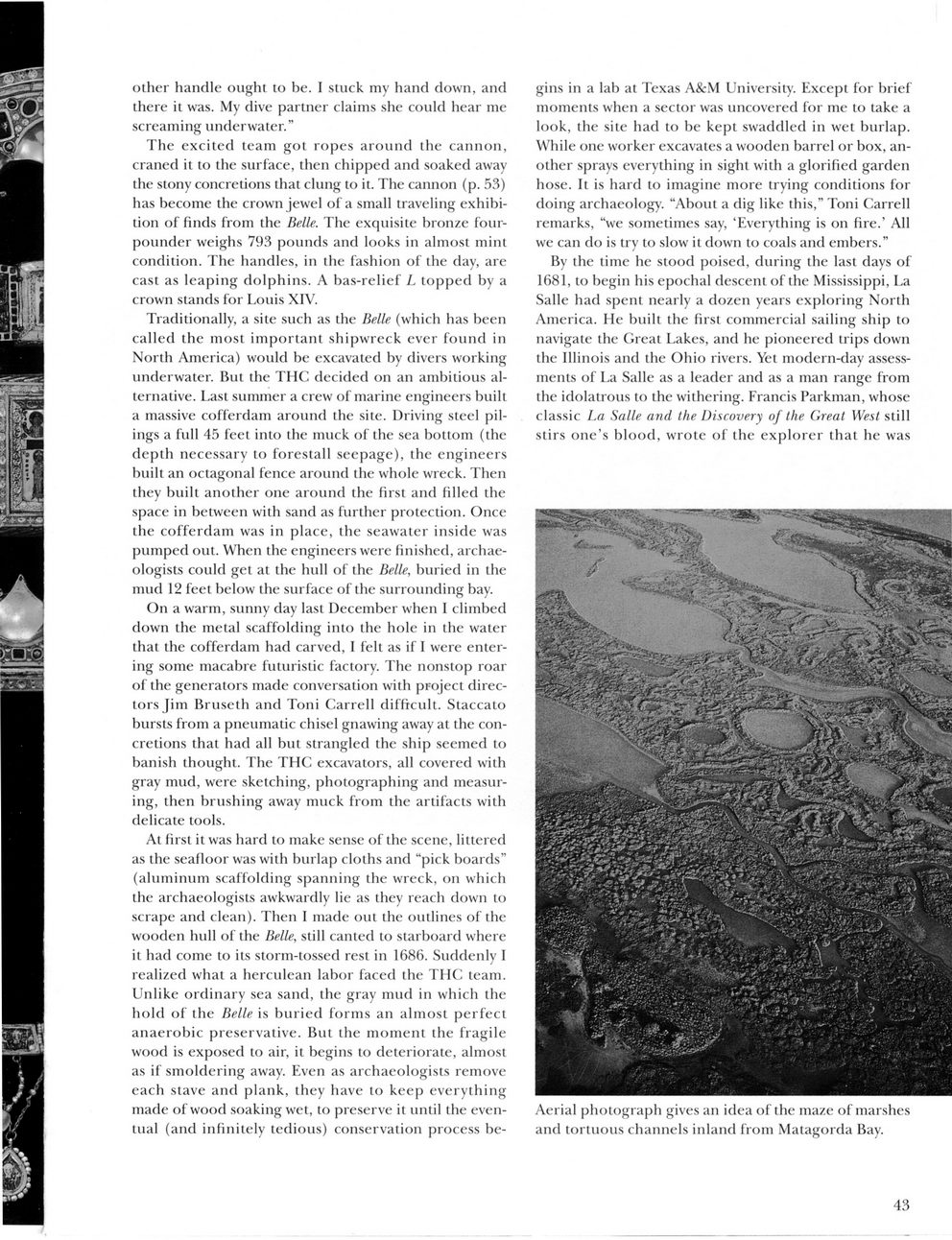

other handle ought to be. I stuck my hand down, and there it was. My dive partner claims she could hear me screaming underwater.? The excited team got ropes around the cannon, craned it to the surface, then chipped and soaked away the stony concretions that clung to it. The cannon (p. 53) has become the crown jewel of a small traveling exhibition of finds from the Belle. The exquisite bronze four-pounder weighs 793 pounds and looks in almost mint condition. The handles, in the fashion of the day, are cast as leaping dolphins. A bas-relief L topped by a crown stands for Louis XIV. Traditionally, a site such as the Belle (which has been called the most important shipwreck ever found in North America) would be excavated by divers working underwater. But the THC decided on an ambitious alternative. Last summer a crew of marine engineers built a massive cofferdam around the site. Driving steel pilings a full 45 feet into the muck of the sea bottom (the depth necessary to forestall seepage), the engineers built an octagonal fence around the whole wreck. Then they built another one around the first and filled the space in between with sand as further protection. Once the cofferdam was in place, the seawater inside was pumped out. When the engineers were finished, archaeologists could get at the hull of the Belle, buried in the mud 12 feet below the surface of the surrounding bay. On a warm, sunny day last December when I climbed down the metal scaffolding into the hole in the water that the cofferdam had carved, I felt as if I were entering some macabre futuristic factory. The nonstop roar of the generators made conversation with project directors Jim Bruseth and Toni Carrell difficult. Staccato bursts from a pneumatic chisel gnawing away at the concretions that had all but strangled the ship seemed to banish thought. The THC excavators, all covered with gray mud, were sketching, photographing and measuring, then brushing away muck from the artifacts with delicate tools. At first it was hard to make sense of the scene, littered as the seafloor was with burlap cloths and ?pick boards? (aluminum scaffolding spanning the wreck, on which the archaeologists awkwardly lie as they reach down to scrape and clean). Then I made out the outlines of the wooden hull of the Belle, still canted to starboard where it had come to its storm-tossed rest in 1686. Suddenly I realized what a herculean labor faced the THC team. Unlike ordinary sea sand, the gray mud in which the hold of the Belle is buried forms an almost perfect anaerobic preservative. But the moment the fragile wood is exposed to air, it begins to deteriorate, almost as if smoldering away. Even as archaeologists remove each stave and plank, they have to keep everything made of wood soaking wet, to preserve it until the eventual (and infinitely tedious) conservation process be- gins in a lab at Texas A&M University. Except for brief moments when a sector was uncovered for me to take a look, the site had to be kept swaddled in wet burlap. WTiile one worker excavates a wooden barrel or box, another sprays everything in sight with a glorified garden hose. It is hard to imagine more trying conditions for doing archaeology. ?About a dig like this,? Toni Carrell remarks, ?we sometimes say, ?Everything is on fire.? All we can do is try to slow it down to coals and embers.? By the time he stood poised, during the last days of 1681, to begin his epochal descent of the Mississippi, La Salle had spent nearly a dozen years exploring North America. He built the first commercial sailing ship to navigate the Great Lakes, and he pioneered trips down the Illinois and the Ohio rivers. Yet modern-day assessments of La Salle as a leader and as a man range from the idolatrous to the withering. Francis Parkman, whose classic La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West still stirs one?s blood, wrote of the explorer that he was Aerial photograph gives an idea of the maze of marshes and tortuous channels inland from Matagorda Bay. 43

LaSalle 004